- Home

- Nancy Mitford

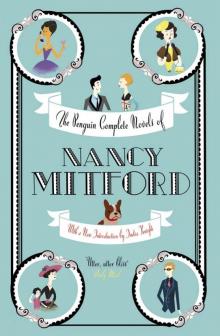

The Penguin Complete Novels of Nancy Mitford

The Penguin Complete Novels of Nancy Mitford Read online

NANCY MITFORD

The Penguin Complete Novels of Nancy Mitford

With a new introduction by India Knight

FIG TREE

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

Contents

Introduction by India Knight

HIGHLAND FLING

CHRISTMAS PUDDING

WIGS ON THE GREEN

PIGEON PIE

THE PURSUIT OF LOVE

LOVE IN A COLD CLIMATE

THE BLESSING

DON’T TELL ALFRED

The Penguin Complete Novels of Nancy Mitford

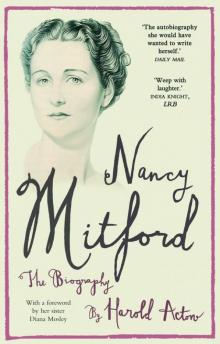

Nancy Mitford (1904–73) was born in London, the eldest child of the second Baron Redesdale. Her childhood in a large remote country house with her five sisters and one brother is recounted in the early chapters of The Pursuit of Love (1945), which, according to the author, is largely autobiographical. Apart from being taught to ride and speak French, Nancy Mitford always claimed she never received a proper education. She started writing before her marriage in 1932 in order ‘to relieve the boredom of the intervals between the recreations established by the social conventions of her world’ and had written four novels, including Wigs on the Green (1935), before the success of The Pursuit of Love. After the war she moved to Paris where she lived for the rest of her life. She followed The Pursuit of Love with Love in a Cold Climate (1949), The Blessing (1951) and Don’t Tell Alfred (1960). She also wrote four works of biography: Madame de Pompadour, first published to great acclaim in 1954, Voltaire in Love, The Sun King and Frederick the Great. As well as being a novelist and a biographer she also translated Madame de Lafayette’s classic novel La Princesse de Clèves into English, and edited Noblesse Oblige, a collection of essays concerned with the behaviour of the English aristocracy and the idea of ‘U’ and ‘non-U’. Nancy Mitford was awarded the CBE in 1972.

India Knight is the author of three novels: My Life on a Plate, Don’t You Want Me? and Comfort and Joy. Her non-fiction books include The Shops, the bestselling diet book Neris and India’s Idiot-Proof Diet, the accompanying bestselling cookbook Neris and India’s Idiot-Proof Diet Cookbook and The Thrift Book. India is a columnist for the Sunday Times and lives in London with her three children.

Introduction

Note: I can’t stand introductions that contain spoilers. There are none here. It’s safe to read, though frankly you would be more than forgiven for skipping forward a bit and jumping straight in. She’s the azure sea; I’m the annoying pebbles that slightly hurt your toes.

There exists a perception that if you like Nancy Mitford, you only like reading gentle period fiction for nice (upper-) middle-class ladies. Either that, or you’re some sort of sinister worshipper at the Shrine of Mitford, blind to the six sisters’ many faults and a-tremble at their legend, wishing that it were the late 1930s and you had a sibling or two with dubious political leanings and a posh mother obsessed with the effect of wholemeal bread upon ‘the Good Body’. But I don’t, as a rule, enjoy fiction for nice ladies (there are exceptions), and I don’t yearn to be reincarnated as a minor aristocrat with an eccentric family. Charming and compelling as the waves of drooling Mitfordiana are and have been, my love of Nancy comes only from admiration of her stupendous talent as a novelist. She’s unbeatable. She is a brilliant writer and a wonderful stylist; she has the beadiest eye – nothing, but nothing, goes unnoticed; she is almost unbearably funny, and she can make you cry at the flick of a page. All this is done so breezily, so apparently effortlessly, so flowingly, that you’d think there was nothing to it at all. Except there is. The novels have real heft, for all their frothy surface: they’re like beautifully iced cakes made of steel, a description that might also apply to Nancy herself.

As well as being reductive, the idea that Nancy Mitford’s books are somehow ‘nice’ conveniently ignores the fact that there was nothing particularly ‘nice’ about Nancy, either in person or in her writing: she was as sharp as a dagger, and cutting was her forte. Her famous ‘teases’ often leave a sting sharp enough to demand the literary equivalent of an EpiPen – as her brother-in-law Oswald Mosley, leader of the British Union of Fascists, found out when a relatively youthful Nancy wrote Wigs on the Green, published in 1935:1

‘I really don’t quite know what an Aryan is.’

‘Well, it’s quite easy. A non-Aryan is the missing link between man and beast. That can be proved by the fact that no animals, except the Baltic goose, have blue eyes.’

Mosley banned Nancy from his home for four years when the book came out, and one can’t imagine that her large, unwieldy sister Unity, who was six foot one and attended deb dances with her pet rat, Ratular – she was also the fascist one who made friends with Hitler before shooting herself in the head on the day England declared war on Germany – was particularly delighted by being caricatured as Eugenia Malmains, ‘England’s largest heiress’ (‘My dog is called the Reichshund, after Bismarck’s dog you know’).

Too much of a deal is also sometimes made of the milieu of Mitford’s novels, as if she had somehow wasted a prodigious talent by writing about people like herself, rather than about weary mothers of twelve living in penury in broken cottages. But she did what good writers do best: write absolutely clear-eyedly and unapologetically about the world she knew back to front and inside out – her own – trusting the reader to be intelligent enough to see that responding to a book has nothing to do with how much, or how little, of your own social circumstances you see reflected within its pages. Mitford is famous for having ‘invented’ U and non-U, where the U stands for ‘upper-class’ usage and the non-U for the aspiring middle-class version. In fact the terms were coined in 1954 by Alan Ross, a professor at the University of Birmingham, as part of a paper on language and social class that was published in a Finnish journal of linguistics. Nancy pounced upon it and used it as the basis for an essay called ‘The English Aristocracy’ for Encounter magazine (there is a wonderful poem/riposte by Ogden Nash called ‘Ms. Found under a Serviette in a Lovely Home’, which I recommend to you). That the world Mitford describes in her books is U is Utterly Undeniable, but what is so remarkable is that she makes it absolutely real, so that, for the duration of your reading journey, it exists and runs in parallel to the world most of us inhabit. Mitford has a particular skill at capturing the reader and drawing her into this fully realized world within about three paragraphs: suddenly – enviably quickly – not only the people but the rooms, the furniture, the dresses, the jewels, the buildings, the food, are absolutely recognizable, even if you knew nothing about them before. Very few novelists since have managed to achieve fully realized worlds in this way unless they are writing fantasy.

Which Nancy, of course, wasn’t. There is escapism, for the modern reader – partly of a nostalgic kind, since the world being described is long gone – and a pleasant sense of becoming historically and anthropologically au fait with the period and its mores; and there are lengthy, heavenly forays into fashion, style and, for want of a better word, glamour. But the reason why these books are so good, so undated, is that they concern themselves with big, universal subjects: family, the past, marriage, love, messy lives, pain. That the people experiencing these things are privileged in the extreme is really neither here nor there; that they’re semi-detached and cope with everything through the medium of jokes ends up seeming like a marvellous way to deal with the perils of life. (Another thing I love about Nancy is her absolute lack of sentimentality. There isn’t one sentimental sentence among these pages,

as befits the woman who wrote, ‘I love children, especially when they cry, for then someone takes them away’.)

And my goodness, the jokes. Such jokes, even now. I remember moving to England, when I was nine years old, and being utterly baffled by the kind of ‘English humour’ I saw on television – these were the mid-1970s, host to The Benny Hill Show and Mind Your Language (tit jokes and jokes about foreigners, respectively, for those of a younger vintage), which I used to sit and watch po-faced, wondering if anything would ever be funny again. It was, of course, but the real revelation came when I picked up The Pursuit of Love aged twelve or thirteen. I thought I would die laughing. I read it, finished it, turned back to page one and started reading it all over again (not something I have ever done again, thousands of books later). To me, The Pursuit of Love and its siblings remain prime examples of all that is best about English humour – the uncontrollable snort of laughter teamed with the wince, the chuckle alongside the sharp intake of breath. The cruelty, I suppose. There’s straightforward comedy within these pages, but more often than not there is a waspishness, a sly knowingness that makes reading them such a particular delight. And never any sign of contrition, or an attempt at tempering or softening the joke, which sometimes falls like a guillotine.

But Mitford is more than a wonderful stylist with a fine line in jokes. She is forensic in her dissection of relationships, and somewhere – buried quite far underneath, I’ll grant you – she has a proper beating heart. The sudden lump in the throat, the rapid blinking that just precedes tears, the image that stays lodged in your head for years after you’ve read the book in question (Linda on her suitcase at the Gare du Nord, Lady Montdore’s blue curls) … these are her trademarks.

This introduction has taken me a paralysingly long time to write, which is not normally how I do things at all. I know exactly why it happened, though: it is because my love of Nancy Mitford is, of itself, paralysing. My admiration is too great, which actually puts me in the creepy position of a kneeling supplicant: try as I might, I can’t find anything to fault in the later novels. Trenchant critique comes there none. I just read and swoon, filled with love, and feeling ninnyishly excited by the idea of you, dear reader, perhaps discovering her for the first time. You know how you sometimes wish you’d never read something by someone, just for the absolute treat of coming across their work in a virgin state? If there’s one person I wish I’d never read, it would be Nancy Mitford, if you see what I mean. I compensate by foisting her on every new person I meet, like a pimp. Were anyone to say, ‘I tried, but it wasn’t really my cup of tea,’ they’d be culled on the spot. Happily, this has yet to happen.

India Knight,

London, September 2011

HIGHLAND FLING

TO HAMISH

1

Albert Gates came down from Oxford feeling that his life was behind him. The past alone was certain, the future strange and obscure in a way that it had never been until that very moment of stepping from the train at Paddington. All his movements until then had been mapped out unalterably in periods of term and holiday; there was never for him the question ‘What next?’ – never a moment’s indecision as to how such a month or such a week would be spent. The death of his mother during his last year at Oxford, while it left him without any definite home ties, had made very little difference to the tenor of his life, which had continued as before to consist of terms and holidays.

But now he stood upon the station platform faced – not with a day or two of uncertain plans, but with all his future before him a complete blank. He felt it to be an extraordinary situation and enjoyed the feeling. ‘I do not even know,’ he thought, ‘where I shall direct that taxicab.’ This was an affectation, as he had no serious intention of telling the taxi to go anywhere else than the Ritz, as indeed a moment later he did.

On the way he pretended to himself that he was trying hard to concentrate on his future, but in fact he was, for the present, so much enjoying the sensation of being a sort of mental waif and stray, that he gave himself up entirely to that enjoyment. He knew that there would never be any danger for him of settling down to a life of idleness: the fear of being bored would soon drive him, as it had done so often in the past, to some sort of activity.

Meanwhile, the Ritz.

An hour later he was sitting in that spiritual home of Oxonian youth, drinking a solitary cocktail and meditating on his own very considerable but diverse talents, when his best friend, Walter Monteath, came in through the swing doors with a girl called Sally Dalloch.

‘Albert, darling!’ cried Sally, seeing him at once, ‘easily the nicest person we could have met at this moment.’

‘How d’you do, Sally?’ said Albert getting up. ‘What’s the matter, why are you so much out of breath?’

‘Well, as a matter of fact it’s rather exciting, and we came here to find somebody we could tell about it; we’ve been getting engaged in a taxi.’

‘Is that why Walter’s face is covered with red paint?’

‘Oh, darling, look! Oh, the shame of it – large red mouths all over your face. Thank goodness it was Albert we met, that’s all!’ cried Sally, rubbing his face with her handkerchief. ‘Here, lick that. There, it’s mostly off now; only a nice healthy flush left. No, you can’t kiss me in the Ritz, it’s always so full of my bankrupt relations. Well, you see, Albert, why we’re so pleased at finding you here, we had to tell somebody or burst. We told the taximan, really because he was getting rather tired of driving round and round and round Berkeley Square, poor sweet, and he was divine to us, and luckily, there were blinds – which so few taxis have these days, do they? – with little bobbles on them and he’s coming to our wedding. But you’re the first proper person.’

‘Well,’ said Albert, as soon as he could get a word in, ‘I really do congratulate you – I think it’s quite perfect. But I can’t say that it comes as an overwhelming surprise to me.’

‘Well, it did to me,’ said Walter; ‘I’ve never been so surprised about anything in my life. I’d no idea women – nice ones, you know – ever proposed to men, unless for some very good reason – like Queen Victoria.’

‘But I had – an excellent reason,’ said Sally, quite unabashed. ‘I wanted to be married to you frightfully badly. I call that a good reason, don’t you, Albert?’

‘It’s a reason,’ said Albert, rather acidly. He disapproved of the engagement, although he had realized for some time that it was inevitable. ‘And have you two young things got any money to support each other with?’ he went on.

‘No,’ said Walter, ‘that’s really the trouble: we haven’t; but we think that nowadays, when everyone’s so poor, it doesn’t matter particularly. And, anyway, it’s cheaper to feed two than one, and it’s always cheaper in the end to be happy because then one’s never ill or cross or bored, and look at the money being bored runs away with alone, don’t you agree? Sally thinks her family might stump up five hundred a year, and I’ve got about that, too; then we should be able to make something out of our wedding presents. Besides, why shouldn’t I do some work? If you come to think of it, lots of people do. I might bring out a book of poems in handwriting with corrections like Ralph’s. What are your plans, Albert?’

‘My dear … vague. I have yet to decide whether I wish to be a great abstract painter, a great imaginative writer, or a great psycho-analyst. When I have quite made up my mind I shall go abroad. I find it impossible to work in this country; the weather, the people and the horses militate equally against any mental effort. Meanwhile I am waiting for some internal cataclysm to direct my energies into their proper channel, whatever it is. I try not to torture myself with doubts and questions. A sidecar for you, Walter – Sally? Three sidecars, please, waiter.’

‘Dear Albert, you are almost too brilliant. I wish I could help you to decide.’

‘No, Walter; it must come from within. What are you both doing this evening?’

‘Oh, good! Now, he’s going to ask us out, which is lovely, isn’t it? Sally darling, because leaving Oxford this morning somehow ran away with all my cash. So I’ll tell you what, Albert, you angel, we’ll just hop over to Cartier’s to get Sally a ring (so lucky the one shop in London where I’ve an account), and then we’ll come back here to dinner at about nine. Is that all right? I feel like dining here tonight and I think we’ll spend our honeymoon here too, darling, instead of trailing round rural England. We certainly can’t afford the Continent; besides, it’s always so uncomfortable abroad except in people’s houses. Drink your sidecar, ducky, and come along.’

‘Cartier will certainly be shut,’ thought Albert, looking at their retreating figures; ‘but I suppose they’ll be able to kiss each other in the taxicab again.’

At half-past nine they reappeared as breathlessly as they had left, Sally wiping fresh marks of lipstick off Walter’s face and displaying upon her left hand a large emerald ring. Albert, who had eaten nothing since one o’clock, was hungry and rather cross; he felt exhausted by so much vitality and secretly annoyed that Walter, whom he regarded as the most brilliant of his friends, should be about to ruin his career by entering upon the state of matrimony. He thought that he could already perceive the signs of a disintegrating intellect as they sat at dinner discussing where they should go afterwards. Every nightclub in London was suggested, only to be turned down with:

‘Not there again – I couldn’t bear it!’

By the time they had finished their coffee Sally said that it was too early yet to go on anywhere, and that she, personally, was tired out and wanted to go home. So, to Albert’s relief, they departed once more, in a taxi.

The next morning Albert left for Paris. It had come to him during the night that he wished to be a great abstract painter.

The Blessing

The Blessing The Sun King

The Sun King Wigs on the Green

Wigs on the Green Love in a Cold Climate

Love in a Cold Climate The Penguin Complete Novels of Nancy Mitford

The Penguin Complete Novels of Nancy Mitford The Pursuit of Love

The Pursuit of Love Frederick the Great

Frederick the Great Highland Fling

Highland Fling Madame de Pompadour

Madame de Pompadour Voltaire in Love

Voltaire in Love Don't Tell Alfred

Don't Tell Alfred Nancy Mitford

Nancy Mitford Christmas Pudding and Pigeon Pie

Christmas Pudding and Pigeon Pie